On Tech Valuations

My apologies for being away for the past month. I was moving from LA to NY and had a lot going on. Anyway, today’s musings (ramblings?) are on this decade’s valuations of technology companies.

Sacha’s Takeaways

- Snap’s recent fall from stock hype is indicative of a much larger problem in technology company valuation

- If users are products, then revenue per user combined with user growth could be a more solid indicator of success than either factor alone

Full Text

Let me predicate the rest of this post with the simple fact that I am not an economist, nor an economics major, nor am I extremely knowledgeable about corporate finance.

Morgan Stanley’s downgrade of Snap’s stock today is what got me thinking about corporate valuations of tech companies. if you haven’t checked the charts for Snap specifically recently, the stock went below IPO for the first time yesterday, and is trading around $15.60 as I am writing this now. While I don’t claim to fully understand why this happened, some brief research plus conversations with friends who are bankers and underwriters has yielded the following: Snap hasn’t innovated fast enough on its advertising revenue model, has suffered from slow user growth, and (this is slightly more controversial) used its IPO earlier this year to keep the company alive financially.

After digging further, my immediate question was “why the hell is this happening now if the stock surged to $26 immediately after hitting the market?” (IPO price was $17). Everyone I’ve asked that question of has come to the same conclusion: the valuation model used to give Snapchat its $22bn valuation prize is inherently flawed, and the initial uptick in share prices reflected non-institutional investors’ confidence in the product, but not the company.

Naturally, today’s case study of Snap got me thinking about the entire system of technology company valuation as a whole (again, I’m not a VC, so please excuse my ignorance in advance). Obviously the traditional model of assets, liabilities, etc. is not very applicable to a company that has few physical assets beyond office space, server/computer hardware, and manpower, but brings in billions in advertising revenue. In recent times, the key factor in replacing those assets (at a rudimentary level) seems to be user base and user growth.

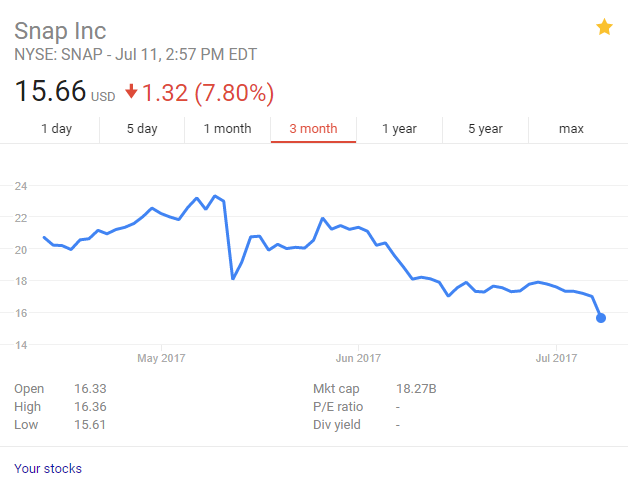

It is interesting that given those two factors alone, Snap’s valuation would have probably been pretty accurate - here’s a chart of daily active user growth from 2014 to 2017:

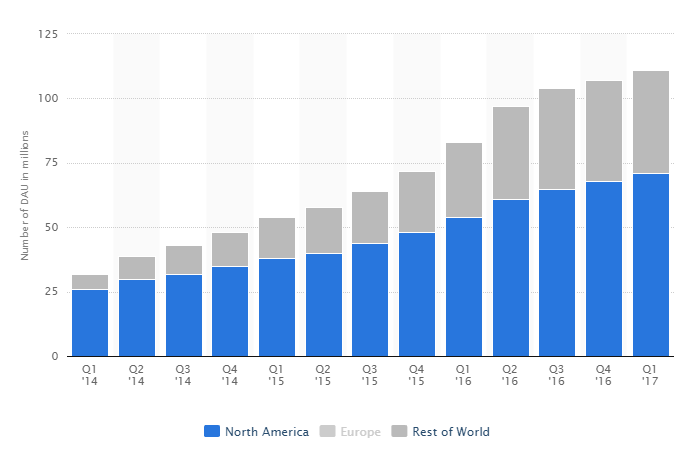

But, then you see this (note that the previous graph was daily active users, and the following is monthly):

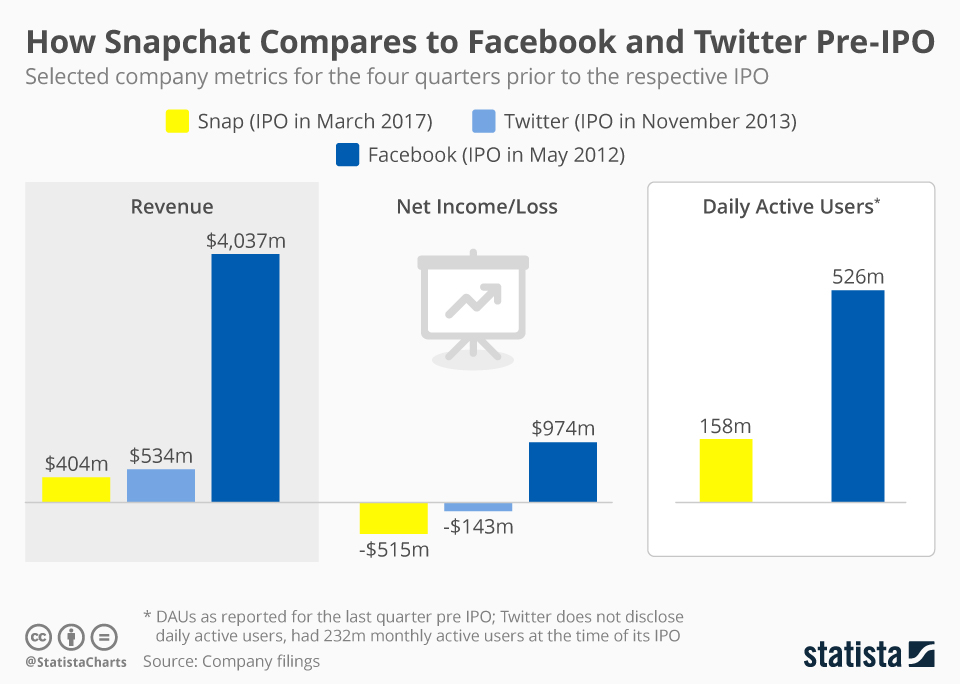

So, Snap did indeed grow fast, and this chart isn’t entirely fair as Facebook (owning every product on that list minus Twitter and Snapchat) is well established and far more globally permeated than Snap is. Unfortunately I couldn’t find a chart comparing Snap’s after-IPO user growth with Facebook’s at the same time in its life, however I did find this:

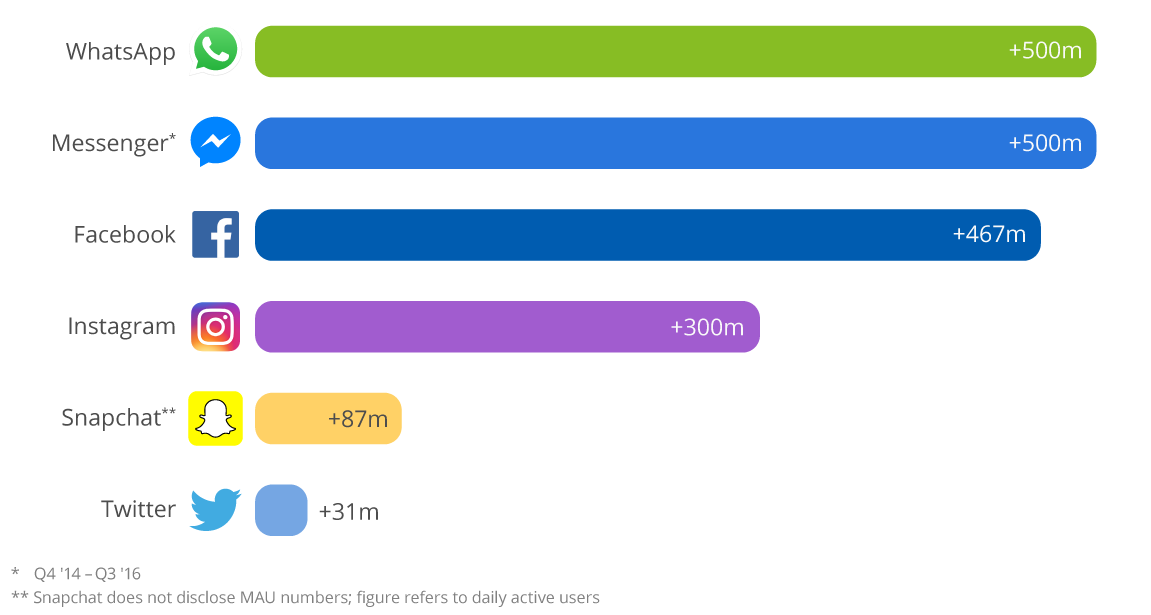

I found this chart to be much more informative - and likely closer to what real finance-types use to value tech companies. Users simply don’t tell the whole story.

If users are the “product” of social networking companies as has been so repeated in the media recently, then shouldn’t we treat a company’s monetization on each user over time as their “assets”?

Given that hypothesis and the previous chart, Facebook revenue per monthly active user was $7.67, and Snap’s was $2.55 (note that this is revenue per MAU, not average revenue per user - Snap reported that as $0.90 in Q1 2017). Even more important, though, is that Facebook actually made money before their IPO (profit of $974m) and Snap STILL lost $515m even given their revenue per user.

My somewhat naive conclusion on all of these ramblings is indeed quite simple: if your product is your user, and you need to make money, then your goals should be to get more users, and make more money from each one without spending too much more to do so. Why don’t we value tech companies on those two factors? And if we do, how did we get to where we are now?

More importantly, why isn’t rampaging over-valuation stopping?

Don’t get me wrong, I work in tech, and I want the industry as a whole to thrive. But in order for that to happen, we need a truer way to value long-term company success.

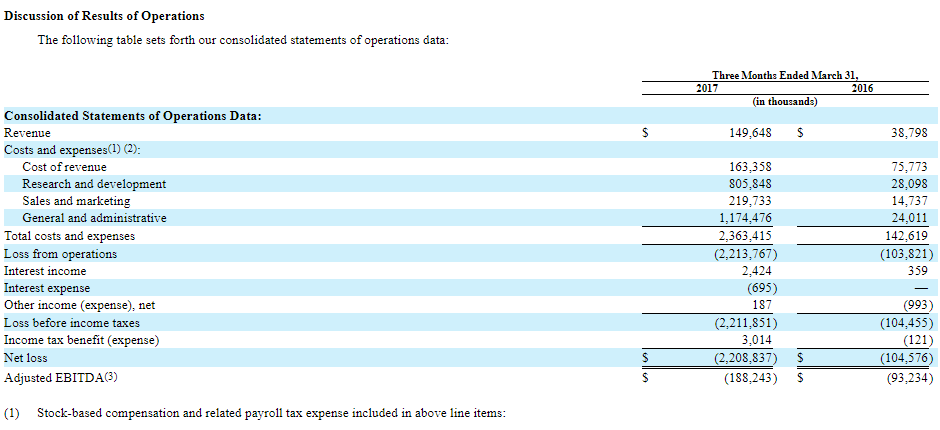

EDIT: can someone explain this to me? Why did $28m in Q1 2016 R&D cost and $24m in administrative expenses go to $805m and $1.2b in Q1 2017? That is a $2.2b loss on less than $200m of revenue.

Comments